By Roger Lowenstein

[1]

“Inauguration Day was cloudy, grim,” wrote Arthur Burns in his diary on Jan. 20, 1969. As he watched President-elect Richard Nixon, Burns—an immigrant from Galicia, the son of a housepainter who had risen to become the foremost expert on U.S. economic cycles and chief economist to Dwight Eisenhower—saw a man with “a look of exaltation about him.” It was not a feeling Burns shared. “I would have felt better if his head were bowed and his body trembled some.”

○inauguration day 大統領就任式当日

○grim 不快な

○president-elect 次期大統領の

○Galicia スペインの一地方

○foremost 一流の

○exaltation 昂揚感

○bow 頭を下げる

○tremble 身震いする

Nixon was inheriting an overheated economy—inflation was already a concern. Burns, 64, would be joining the Administration as a uniquely trusted adviser. In 1960, when then Vice-President Nixon was seeking the White House, Burns had warned him that if the Federal Reserve tightened interest rates, it could damage Nixon’s chances. It had played out just so: The Fed tightened, the economy suffered a recession, and Nixon lost to John F. Kennedy. Nixon never forgot the power of the Fed, and he remembered Burns as an economist with political savvy.

○inherit 相続する

○overheated 過熱した

○inflation 通貨膨張、物価上昇

○concern 心配事

○administration 内閣、政権

○the Federal Reserve 連邦準備制度事会(米国中央銀行)

○tighten 引き締める

○interest rates 公定歩合

○play out 演じきる、遂行する

○suffer 苦しむ

○recession 一時的な景気後退

○political savvy 経済の専門知識

So it was that a year into his term, with the economy faltering, Nixon tapped Burns to replace William McChesney Martin Jr., the Fed chief who had dashed his hopes in 1960. According to Burns biographer Wyatt Wells, Nixon issued his appointee some blunt instructions: “You see to it,” Nixon said. “No recession.”

○falter よろめく、不安定になる

○tap A to(do) Aに~を求める

○replace 入れ替える

○dash one's hopes 希望を打ち砕く

○according to によると

○biographer 伝記作家

○issue A ~ instruction Aに~な指示をする

○appointee 被任命者

○blunt 無遠慮な、ぶしつけな

○see to it 面倒を見る、責任を持つ

Burns had more to address than a faltering economy and a famously meddlesome patron. By December 1969, inflation had topped 6 percent—its highest level since the Korean War. Inflation had disturbing international implications because, in the system known as Bretton Woods that had prevailed since the end of World War II, the U.S. was committed to backing every dollar overseas with gold. Thus, foreign countries had the right to exchange their greenbacks at the rate of $35 per ounce. The other currencies were fixed to the dollar, and the dollar—the sun in the monetary sky—was pegged to gold.

○famously meddlesome お節介で有名な

○patron 後援者、恩人、主人

○by までには

○top に達する

○the Korean War 1950年勃発の朝鮮戦争

○disturb 乱す、妨げる、迷惑を掛ける

○implications 緊密な関係、暗示

○Bretton Woods ドル基軸通貨体制(金本位制)

○prevail 普及する

○be committed to -ing 使命感を持って取り組む

○back 支える

○right 権利

○exchange greenbacks 米ドル札を交換する

○at the rate of の割合で

○per ounce 金1オンス当たり

○be fixed to the dollar ドルに固定される

○the sun in the monetary sky 通貨市場の太陽

○be pegged to に通貨を固定する

For the first years after World War II, Bretton Woods (named for the New Hampshire resort where delegates from 44 Allied nations met in 1944) worked perfectly. Japan and Europe were still rebuilding, and foreigners were eager for dollars they could spend on American cars, steel, and machinery. Even as they accumulated currency reserves, America’s trading partners were content to park them in interest-bearing dollars rather than in inert metal. And since the U.S. owned over half the world’s official gold reserves—574 million ounces at the end of World War II—the system seemed secure.

○the New Hampshire resort ニューハンプシャー州のリゾート地

○delegates 代表団

○Allied nations 同盟諸国

○rebuilding 復興中

○be eager for を熱心に求める

○spend on に費やす

○steel 鉄鋼

○machinery 機械類

○accumulate を蓄積する

○currency reserves 外貨準備

○be content to(do) するのに満足している

○park A in B AをBに留める

○interest-bearing dollar 利息を生むドル

○A rather than B BよりむしろA

○inert metal 値動きの鈍い金属(黄金)

○since ので

○own 所有する

○official gold reserves 公式の金の備蓄

○seem secure 万全だと思われる

But from 1950 to 1969, as Germany and Japan recovered, the U.S. share of the world’s economic output fell decisively, from 35 percent to 27 percent. Other nations had less need for dollars and more for Deutsche marks, yen, and francs. Also, U.S. spending on Vietnam and domestic programs flooded the world with dollars. Bit by bit, America’s allies began to ask for gold.

○Germany ドイツ

○recover 復興する

○share 市場占有率

○economic output 経済的生産高

○fall 下落する

○decisively 決定的に

○have less need for の必要性が低下する

○Deutsche marks ドイツ通貨マルク

○francs フランス通貨フラン

○Vietnam ベトナム(戦争)

○domestic programs 国内政策

○flood A with B AをBで溢れさせる(過剰供給)

○bit by bit 徐々に

○America's allies 米国の同盟国

○ask for を要求する

The official charged with monitoring gold and other international exchanges was the Undersecretary for Monetary Affairs, a gruff, 6-foot, 7-inch banker named Paul Volcker. He had been worried about the gold market for quite some time. Although the U.S. fixed the official gold price, a market existed in London, in which, in effect, companies sold metal to jewelers and dentists, with central banks sopping up the surplus. Generally, the banks kept the price near to $35. One day in 1960, when Volcker was working at Chase Manhattan, someone burst into his office with news: Gold was at $40(米ドルの価値が5ドル下落). Volcker couldn’t believe it. The price receded, but it was a worrisome foretaste. Jitters in the gold market were an early symptom of domestic inflation.

○official 係官

○charged with の責任を負う

○monitor を監視する

○international exchanges 国際為替

○undersecretary 次官

○Monetary Affairs 金融財務

○gruff がっちりした

○banker 銀行員

○for some time しばらく

○although けれども

○fixed 固定する

○market 市場

○existed 存在していた

○in effect 実際には、事実上

○sell A to B AをBに売る

○metal 金属

○jewelers and dentists 宝石商や歯科医

○with O+C OがCして

○central banks 中央銀行

○sop up 吸い取る

○surplus 余剰金、黒字分

○generally 一般的に

○keep 保つ

○the price (金の)価格

○near to 近くに

○one day ある日

○Chase Manhattan チェースマンハッタン銀行

○burst into 慌てて~に入ってくる

○at の価格で

○recede 退く、低下する

○worrisome foretaste 心配な前兆

○jitters 揺らぎ、乱れ、不安感

○an early symptom 早期の兆候

○domestic inflation 国内のインフレ

By the time Nixon took office, officials knew they were sitting on a powder keg. As Volcker, then 41, recalls, he warned incoming Treasury Secretary David M. Kennedy that they had two years to save the dollar. America’s balance of payments deficit in 1969 had reached $7 billion—small by today’s standards but scary then.(米国の対外貿易赤字は巨大化し大量のドル=金が流出するのでまずい) This meant more dollars accumulating in London, Bonn, and Tokyo. Volcker pressed the Europeans to revalue their currencies(各国通貨の価値を上げることで相対的にドルの価値を下げる); if Americans had to pay more for French wine, fewer dollars would pile up overseas.(ドルの価値が下がればドルの海外資産価値も減る→金の流出を防ぐ、金本位制ゆえの問題) Germany modestly revalued; others refused. The Europeans, as well as Japan, were caught in a trap: They were reluctant to hold dollars(ドルは相場が切り下げられるので持っていたくない=ドルの量は減らしたい), but unwilling to give up their dependence on exporting goods to America.(でも消費旺盛な市場としての米国は魅力的=ドルがますます増えてしまう、というジレンマ)

○by the time S+V SがVする頃までには

○take office 執務を開始する

○sit on a powder keg 火薬樽の上に座る

○recall 回想する

○warn 警告する

○incoming 後任の

○Treasury Secretary 財務長官

○save the dollar ドルを救う

○balance of payments deficit 国際収支の赤字

○by today's standards 今日の基準では

○scary then 当時は恐かった

○meant 意味していた

○accumulating 蓄積している

○press A to(do) Aに~するよう圧力をかける

○the Europeans 欧州各国

○revalue 再評価する、平価を上げる

○currencies 通貨

○modestly 謙虚に

○others = other countries 他の国々

○refuse 拒否する、拒絶する

○B as well as A A同様にBもまた

○be caught in a trap 罠にはまる、落とし穴にはまる

○be reluctant to(do) ~するのには消極的だ

○hold dollars ドルを持ち続ける

○be unwilling to(do) ~するのは気が進まない

○give up 諦める、放棄する

○dependence on ~への依存

○export A to B AをBに輸出する

○goods 商品

[2]

Nixon had minimal patience for the details of international finance. When an aide informed him of monetary problems in Rome, Nixon snapped, “I don’t give a s— about the lira.” What he did care about was the domestic economy, especially the politically sensitive unemployment number. And despite his instructions to Burns, in 1970 the U.S. suffered a recession, triggering a rise in unemployment to 6 percent, its highest mark in a decade.

○minimal 最小限の

○patience 忍耐力

○details 詳細

○international finance 国際金融

○an aide 補佐官

○inform A of B AにBを知らせる

○monetary problems 金融問題

○snap ぶしつけに言う

○give a suck 俗語(スラング)

○the lira イタリア通貨リラ

○care about 気にかけていた

○domestic economy 国内経済

○especially 特に

○politically sensitive 政治的に敏感な

○unemployment number 失業率

○despite にもかかわらず

○instruction 指示

○suffer で苦しむ

○recession 景気後退

○trigger a rise in の上昇の引き金を引く

○highest mark 最高値

○decade 十年

Nixon was furious with Burns. He began taking economic cues from George

Shultz, the Labor Secretary and then Budget Director. Shultz argued that Burns

had erred by limiting the expansion of the money supply, which over the course

of 1970 was less than 4 percent. Shultz, a former business school dean at

Chicago, was echoing the theories of his close friend, Milton Friedman, the

architect of the Chicago School. To Friedman, money supply was the single key

tool at the Fed’s disposal. Friedman viewed money in terms of supply and demand:

If the Fed printed more dollars, then money would be worth less and goods would

cost more, i.e. inflation. But he also saw overly tight money as having worsened

the Great Depression.

○be furious with に激怒している

○take economic cues from から経済政策的助言を受ける

○the Labor Secretary 労働大臣

○Budget Director 行政管理予算局局長

○argue 主張する

○err 誤る

○by -ing することによって

○limit 制限する

○expansion 拡大

○the money supply 通貨供給

○over the course of の間ずっと

○former 元

○business school dean ビジネススクール学部長

○echo をそっくりまねる

○theory 理論

○close friend 親友

○Milton Friedman ミルトン・フリードマン(ノーベル経済学賞受賞者)

○architect 設計者

○the Chicago School シカゴ学派

○single 唯一の

○key tool 重要な道具

○at one's disposal の自由裁量権にある

○view A in terms of B AをBの観点から見なす

○supply and demand 供給と需要

○the Fed 連邦準備制度委員会(米国中央銀行)

○print more dollars もっとドル札を刷る

○worth less 価値がより低下する

○cost more さらにコストがかかる

○i.e. = for example 例えば

○inflation 通貨膨張、物価上昇

○but also ~とも

○see A as B AをBと見なす

○overly 過度に

○tight money 引き締められた通貨量

○having p.p. ~していたと

○worsen さらに悪化させる

○the Great Depression 1929年の大恐慌

Burns, only eight years older than Friedman, had taught Friedman at Rutgers and been a mentor to him since. The two maintained a close friendship, and their families summered at nearby homes in Vermont. However, Burns didn’t share the rigid Friedman-Shultz belief that the money supply was everything. Burns distrusted single-answer diagnoses and blamed inflation partially on other factors, such as the growing power of labor unions. When even the 1970 recession failed to curb inflation, Burns was stumped. “What the boys around the White House fail to see,” Burns scribbled in his diary, “is that the country now faces an entirely new problem—sizable inflation in the midst of recession.” As Burns would tell a congressional committee, “The rules of economics are not working the way they used to.” Prices were going up even when factories stood idle—a seeming refutation of the economic rules.

○Rutgers ラトガース大学

○mentor 師匠

○maintain 保つ、維持する

○a close relationship 親しい関係

○summer 夏を過ごす、避暑をする

○nearby すぐそばの、近くの

○Vermont バーモント州

○share 分かち合う、共有する

○rigid 硬直した、厳格な

○belief that S+V SがVするという信念、考え

○distrust 信用しない

○single-answer 単一解答の

○diagnose 診断

○blame A on B AをBのせいにする

○partially 部分的に

○factor 要因

○such as 例えば~の様な

○growing power 成長著しい勢力

○labor unions 労働組合

○fail to(do) するのに失敗する、できなくなる

○curb 抑制する

○be stumped お手上げになる

○what S+V SがVすること、もの

○the boys 年下の連中

○around the White House ホワイトハウス(米国大統領官邸)の周囲をうろつく

○scribble 書き殴る、書き散らす

○diary 日記

○is that S+V SがVするということだ

○face に直面する

○entirely new 全く新しい

○sizable inflation かなり大きいインフレ

○in the midst of の真っ最中の

○recession 景気後退

○as S+V ように

○would よく~した

○a congressional committee 連邦議会の委員会

○the rules of の法則

○economics 経済学

○work 働く、作用する

○the way S+V SがVする様に

○used to(do) 以前~した

○prices 物価

○go up 上昇する

○even when S+V SがVする時でさえ

○factory 工場

○stand idle 停止したままでいる

○seeming 外見上は

○refutation 反論、反駁

○the economic rules 経済学法則

Despite the galloping inflation, Nixon pressured Burns to loosen monetary policy. White House aides, violating the central bank’s supposed independence, inundated the Fed with memos on the need to lower rates. “The pressure that Nixon exerted was unbelievable,” says Joseph Burns, the late Fed chief’s son. Volcker agrees that it got “very rough.”

○despite にもかかわらず

○galloping 馬がはねるような、急激な

○pressure A to(do) Aに~するよう圧力をかける

○loosen ゆるめる、緩和する

○monetary policy 金融政策

○White House aides 大統領補佐官

○violate に違反する

○the central bank 中央銀行

○supposed 想像上の、仮定上の、単にうわべだけの

○independence 独立性

○inundate A with B AをBで氾濫させる、水浸しにする

○memo = memorandum 覚書、備忘録、連絡メモ

○on the need to(do) ~する必要に関する

○lower 引き下げる

○rates 公定歩合

○exert 行使する

○unbelievable 信じられない

○late 故

○the Fed chief 連邦順制度理事会理事長

○agree that S+V SがVすると同意する

○get rough 乱暴だ

As the economy shifted into a tepid expansion in ’71, Burns allowed the money

supply to expand at an annual rate of 8 percent in the first quarter, 10 percent

in the next. This was wildly expansionary. Allan Meltzer, a Fed historian, says

Burns’s policy was partly attributable to honest miscalculations. (Determining

the rate of money supply growth is fiendishly difficult.) But Meltzer says Burns

was also influenced by Nixon’s bullying. The President alternately flattered

Burns and excluded him, and Burns careened between feisty shows of independence

and toadying displays of loyalty. In his diary, Burns assures the President that

“his friendship was one of the three that has counted most in my life”; a few

months later he is recoiling at Nixon’s “cruelty” and, still later, at his

anti-Semitic outbursts. He feared the consequence of higher unemployment, yet

was committed to the success of the Nixon Administration. This conflict led

Burns to a dramatic about-face. In 1970, the Democratic-led Congress had

authorized the President to impose wage and price controls. Nixon, who had

played a small role in administering war-time price controls while working for

the Office of Price Administration, thought they wouldn’t work. The issue became

a political football. Then, at the end of 1970, Burns gave a speech advocating a

wage and price review board that would issue guidelines and try to restrain

inflation through suasion and public statements. Milton Friedman regarded it as

an endorsement of centralized planning—and a personal betrayal. He stayed up all

night writing his mentor what, he said later, was an overly harsh letter; Burns

and Friedman were never friends again.

○as S+V SがVするにしたがって

○shift into に移転する、変化する

○tepid なまぬるい

○expansion 拡大

○allow A to(do) Aが~するのを許す、Aが~できるようにする

○at an annual rate of 年間~の割合で

○the first quarter 第1四半期(1月~3月)

○the next (quarter) 第2四半期(4月~6月)

○wildly 乱暴に、激しく、野性的に

○expansionary 拡大性の、膨張性の

○a Fed historian 連邦準備制度理事会を研究する歴史家

○partly 部分的に

○be attributable to に要因がある

○honest 正直な、悪意のない

○miscalculations 計算ミス

○detemine 決定する

○the rate of の割合

○money supply growth 通貨供給量の増加

○fiendishly 非常に、恐ろしく

○be influenced by の影響を受ける

○bullying いじめ、嫌がらせ

○alternately 交互に、代わる代わる

○flatter を褒める、おだてる、おもねる

○exclude 除外する、排除する

○careen 傾く

○between A and B AとBの間で

○feisty 子犬のようにはしゃぐ、元気の良い

○independence 独立性

○toady にへつらう、ぺこぺこする、機嫌を取る

○shows = displays 感情表現

○loyalty 忠誠心

○assure A that S+V SがVするといってAを安心させる

○friendship 友情

○count most 最も重要だ

○recoil at にひるむ

○cruelty 冷酷さ、残酷さ、無慈悲さ

○anti-Semitic 反ユダヤの、反セム系の

○outburst ほとばしる感情、激情

○fear を恐れる

○consequence 結果、帰結、重要性

○yet しかしそれでも

○be committed to を危うくする、に累を及ぼす

○success 成功

○conflict 衝突

○lead A to B AをBに導く、至らしめる

○dramatic 劇的な

○about-face 転向、変節、回れ右

○the Democratic-led Congress 民主党主導の連邦議会

○authorize A to(do) Aに~する権限を与える

○impose を課す、乱用する

○wage and price controls 労働賃金と物価の管理

○play a small role in に大きな役割は果たさない

○administer を運営する、処理する

○war-time price controls 戦時中の物価管理

○work for で働く

○the Office of Price Administration 物価管理局

○wouldn't work うまくいかない

○issue 争点、問題

○political football 政治的なゲーム、駆け引き

○at the end of の終わりに

○give a speech -ing ~する演説を行う

○advocate 支持する、弁護する、擁護する

○a review board 再検討委員会

○issue guidelines 指針を示す

○restrain を規制する、抑制する

○through suasion and public statement 勧告と声明を通じて

○regard A as B AをBと見なす

○endorsement 裏書き、是認、承認

○centralized planning 中央政府による策定

○a personal betrayal (フリードマンへの)個人的な裏切り行為

○stay up all night 徹夜する

○write に手紙を書く

○what S+V SがVすること、もの

○overly harsh 過剰に粗暴な

[3]

In the first half of 1971, unions representing copper, steel, and telephone workers negotiated wage increases of more than 30 percent over three years, in addition to cost-of-living adjustments. To modern readers, it may seem odd that the chairman of the Federal Reserve was reluctant to raise interest rates in the teeth of double-digit inflation, but the modern view that only the Fed can control inflation was not widely accepted. Balanced budgets were thought to be of equal importance. And, as Meltzer notes, few Americans thought inflation was worth sacrificing jobs for. That summer, Time magazine opined that, “once an inflation starts, no government could accept the severe recession and unemployment needed to stop it cold.” This was the conventional view—that the Fed was powerless.

○unions 労働組合

○representing を代表する

○copper, steel, and telephone 銅・鉄・電話

○negotiate を交渉する

○wage increase 賃上げ

○in addition to に加えて

○cost-of-living adjustiment 生計費調整

○modern readers 現在の読者

○seem odd 奇妙に感じられる

○the chairman of FRB 連邦準備制度理事会議長

○be reluctant to(do) ~するのに消極的だ

○in the teeth of の猛威の中で

○double-digit 2桁の

○modern view 現代の考え方

○control inflation インフレを抑制する

○be widely accepted 広く受け入れられる

○balanced budget 均衡のある予算

○be of equal imoortance 同等に重要である

○note 特に言及する

○few Americans アメリは人はほとんどいない

○be worth -ing ~する価値がある

○sacrifice A for B AをBの犠牲にする

○Time magazine タイム誌

○opine 意見を申し述べる

○once S+V いったんSがVすれば

○no governmnet could ~できる政府はない

○accept 受け入れる

○severe 厳しい、猛烈な、過酷な、血も涙もない

○unemployment need to(do) ~するのに必要となる失業

○stop it cold それを完全に止める

○conventional view 伝統的な考え方

○powerless 無力な

Friedman argued that it was better to snuff out inflation because, in the long run, inflation (which merely amounted to printing money) wouldn’t truly create jobs. Friedman’s position was later to become gospel. At the time, though, many economists believed that by adding to the money supply, the central bank could spur growth. Burns, therefore, urged the White House to curb inflation by non-monetary means. He encouraged the President to “jawbone” industries to show restraint and to form a council of wise men who would publish guidelines. Nixon feared guidelines were a step toward controls; his solution was to bring inflation down without a recession, by working toward a balanced budget. Herbert Stein, his economic adviser, told him flatly it wouldn’t work. Burns chafed: “I am convinced that the President will do anything to be reelected.”

○argue that S+V SがVすると主張する

○snuff out 鎮圧する、消滅させる

○in the long run 長期的に見れば

○be amounted to に達する

○printing money お札を刷る

○not truly 必ずしも~ない

○create jobs 仕事を生み出す

○gospel 福音

○though けれど

○economist 経済学者

○by -ing ~することによって

○add to を増やす

○money supply 通貨供給量

○the central bank 中央銀行

○spur に拍車をかける、を刺激する

○growth 成長

○therefore ゆえに

○urge A to(do) Aが~するよう促す

○curb 規制する、抑制する

○by non-monetary means 非金融的な手段で

○encourage A to(do) Aが~するよう促す、励ます

○the President 大統領

○jawbone 大統領が自ら説得工作をする

○industries 産業界

○restraint 抑制、自制

○form a coucil of wise man 賢人会議を作る

○publish guidelines 指針を公表する

○fear (that) S+V SがVすると恐れる

○a step forward to ~への一歩

○control 規制、管理

○solution 解決策

○bring A down Aを下げる

○without なしで

○work toward を目指して励む

○economic adviser 経済政策助言者

○flatly きっぱりと、平らに

○work うまくいく

○chafe いら立つ

○be convinced that S+V SがVすると確信している

○be reelected 再選する

Rampant domestic inflation was mirrored, franc for franc, in markets overseas. Foreign governments intervened to buy dollars to shore up America’s currency (and their export trade). This left their central banks swollen with greenbacks. “Foreigners buying dollars caused a monetary expansion, similar to today,” says Ronald McKinnon, an economist at Stanford University. Meanwhile, America’s gold stock had dwindled to $10 billion, half its 1960 level. The gold standard now existed only in name, for foreign banks held far more dollars than the U.S. held gold. This left the U.S. vulnerable to a run.

○ranpant 激しい

○domestic inflation 国内のインフレ

○be mirrored 鏡写しになる

○franc for franc フランに対するフラン

○overseas 海外の

○foreign governments 外国政府

○intervene 介入する

○shore up 支える、強化する

○currency 通貨

○export trade 輸出貿易

○leave O+C OをCのままにする

○swollen with で膨れあがった、膨張した

○greenbacks (裏が緑色の)米ドル札

○cause a monetary expansion 通貨膨張を引き起こす

○similar to に類似して

○Stanford University スタンフォード大学

○meanwhile その間、一方で

○gold stock 金のたくわえ

○dwindle to へとだんだん減っていく

○half 二分の一

○level 水準

○the gold standard 金本位制

○exist only in name 名ばかりの存在である

○for S+V ので

○hold 所持している

○far more A than B Bよりずっと多くのA

○leave O+C OをCのままにする

○vulnerable to に脆弱な

○a run (銀行の)取り付け

With shrewd timing, in early 1971, Nixon appointed a new Treasury Secretary, John Connally, a hulking former Texas governor, who saw these various financial trials—inflation, the pressure on the dollar, the mounting trade deficit—as affronts to the national honor. It was the peak of the Vietnam protest movement, and Connally felt the U.S. had absorbed enough humiliations. He had no abiding economic philosophy; as he proclaimed to Nixon, “I can play it square, I can play it round, just tell me how you want me to play it.” What he brought to the Nixon team was enormous ego, force of personality, and a political intuition that economic reforms, which appeared imminent, had to be presented in a program acceptable to ordinary Americans. That Connally lacked financial expertise bothered him not a whit. “I can add,” he said upon taking the job. His role, as he saw it, was to pull together the competing recommendations of Shultz, Burns, and Volcker into a policy suggesting coherence.

○shrewd timing 抜け目のないタイミング

○appoint 指名する

○Treasury Secretary 財務長官

○hulking 大柄な、図体の大きな

○former 前

○Texas governor テキサス州知事

○various 様々な、色々な

○financial trials 財政的ないくつもの試練

○pressure on への圧力

○mouting 積み上がる

○trade deficit 貿易赤字

○as として

○affronts 公然たる侮辱、無礼

○the national honor 国家的名誉

○the peak of の頂点

○Vietnam protest movement ベトナム反戦運動

○absorb 吸収する

○humiliations 恥、屈辱

○abiding 長期にわたる、永続的な

○enocomic pholosophy 経済哲学

○proclaim to に宣言する、宣告する

○can play it square 四角にもできるし

○can play it round 丸にもできる

○how S+V どのようにSがVするか

○want A to(do) Aに~してもらいたいと思う

○bring to にもたらす

○the Nixson team ニクソン政権

○anormous ego 巨大なエゴ

○force of personality 個の力

○a political intuition 政治的直感

○economic reforms 経済改革

○appear ように思われる

○imminent 切迫した

○be presented 提示される

○in a program acceptable 受け入れ可能な形で

○ordinary Americans 一般的な米国人

○lack が欠ける、欠如する

○financial expertise 財政的専門知識

○bother を悩ます

○not a whit 微塵も~ない

○upon -ing ~するとすぐに

○take the job 仕事に就く

○role 役割

○was to(do) ~することだった

○pul together A into B AをBにまとめ上げる

○competing recomendations 互いに競合しあう提案

○a policy 一つの政策

○suggest 暗示する、示唆する、ほのめかす

○coherence 結合力、統一性、首尾一貫性

Burns continued to back a wage council; he also thought the U.S. should devalue against gold (that is, raise the gold price above $35). Volcker believed this would be ineffectual, as other countries would simply devalue their currencies by the same percentage. To Volcker, the key to restoring balance was a 10 percent-to-15 percent devaluation of the dollar against the yen and the European currencies. Even if America’s allies refused to budge, Volcker thought the U.S. could force the issue by temporarily halting gold-dollar convertibility.

○continue to(do) ~し続ける

○back を支える

○a wage council 賃金審議会

○devalue against に対する価値を下げる、平価を切り下げる

○that is すなわり

○raise を上げる

○gold price 金の価格

○above より上に

○ineffectual 効果がない

○as S+V ので

○simply 単に

○by the same percentage 同じ割合で

○the key to への鍵

○restore を回復する

○balance 均衡

○devaluation 価値引き下げ、平価切り下げ

○the European currencies 欧州通貨

○even if S+V たとえSがVするとしても

○allies 同盟国

○refuse to(do) ~するのを拒絶する、拒否する

○budge 譲歩する

○force 強制する

○the issue 問題

○by -ing ~することによって

○temporarliy 一時的に

○halt 停止する

○gold-dollar convertibility 金とドルの交換

[4]

The pressure intensified that spring. In April and into May, as speculators sold dollars and hoarded deutsche marks, Germany was forced to purchase $5 billion to stabilize the exchange rate. This was a huge sum in an era in which hedge fund goliaths did not exist. On May 5, Germany caved to the upward pressure on its currency and let the deutsche mark float. This brought the West a step closer to Friedman’s dream of freely trading currencies, but it did not alleviate the crisis.

The gold exodus continued and, to make matters worse, the U.S. began running a substantial trade deficit, a politically charged issue given that unemployment remained at 6 percent. Nixon had to act, but his advisers were split. Volcker, as well as Shultz, wanted to close the gold window. Burns was vehemently opposed. Severing the gold link would turn money into … paper. If the government no longer had to preserve the dollar’s value in metal, how could the Administration claim, with any credibility, to be countering inflation?

This question prompted officials to give controls a second look. No one in the Administration, from Nixon down, believed in controls in an economic sense. They were Sovietized economics, an attempt to force markets where they didn’t want to go. But the economics didn’t matter to Connally; what counted was a forceful display of power. Over the summer, Connally, with Nixon present, briefed Shultz—essentially so the latter could air his objections and then get behind the program. Secrecy was imperative. “Don’t tell your wife,” Nixon warned Shultz.

The intent was to move after Labor Day, but on Aug. 12, a Thursday, Britain stunned the U.S. by demanding that it guarantee the value of $750 million. On Friday, Nixon summoned 15 advisers to Camp David; he insisted no outsiders be told. Volcker wisely took exception and briefed a colleague in the State Dept. and also the Japanese. Stein, the economic adviser, told William Safire, the speechwriter, that they were embarking on the most momentous economic decision since March 1933. “[Are] We closing the banks?” Safire asked. Stein said no, but the gold window might be disappearing. “What a tragedy for mankind,” wrote Burns in his diary.

The plan, presented by Connally, had three key points. First, America would stop converting dollars to gold. Second, to combat the potential inflationary effects, wages and prices would be frozen for 90 days. And third, the U.S. would impose an import surcharge of 10 percent. Connally’s idea was to use the surcharge as a cudgel, to pressure other countries to renegotiate their exchange rates.

The Camp David weekend was intended for Connally to get everyone’s support before the program was announced. People slept two to a cabin (the bed was too short for Volcker) and convened in the dining room. Nixon remained cloistered in his cabin, the Aspen Lodge, but called anxiously for updates. Burns spent an evening pacing the grounds with Volcker, wringing his hands over the gold standard. Burns alone was invited to the President’s cabin for a private audience. Although Nixon regarded the pipe-smoking Fed chairman as pompous and long-winded, he knew Burns was trusted by the public, and he needed his support. Otherwise, it was Connally’s show.

Connally brilliantly packaged the program not as America abandoning its commitment to the gold standard but as America taking charge. He turned the dollar’s collapse, which could have appeared shameful, into a moment of hubris. The emphasis would be on righting America’s trade balance, as well as minor points such as a 5 percent cut in foreign aid. An aide to William P. Rogers, the Secretary of State, called and interjected, “You can’t cut foreign aid.” Connally said, “Tell him if he doesn’t shut up we’ll make the cuts 15 percent.” Shultz muzzled his disquiet over price controls; even Burns joined ranks. The group feverishly debated whether Nixon should address the country on Sunday night, which would mean preempting the popular Gunsmoke. The public relations aspect was paramount. Stein wrote later that the discussion at Camp David assumed “the attitude of scriptwriters preparing a TV special.” No one pretended to know how controls would work; the question was scarcely debated.

[5]

Addressing the nation on Sunday, Nixon blamed currency speculators and “unfair” exchange rates rather than U.S. monetary policy. Politically, he hit the jackpot. Monday’s nearly 33-point rise in the Dow was the biggest ever to that point. Nixon’s “New Economic Policy” drew raves from the press. “We unhesitatingly applaud the boldness with which the President has moved,” read the New York Times editorial. In the present era, America’s inability to repair its fiscal problems has tarnished its credibility and hampered its currency negotiations with China. The Nixon Shock showed the U.S. taking action. That December, Shultz and Volcker successfully negotiated a broad revaluation of exchange rates.

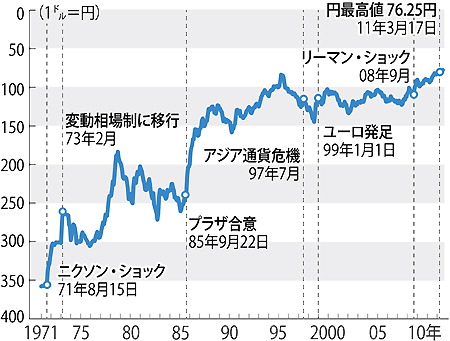

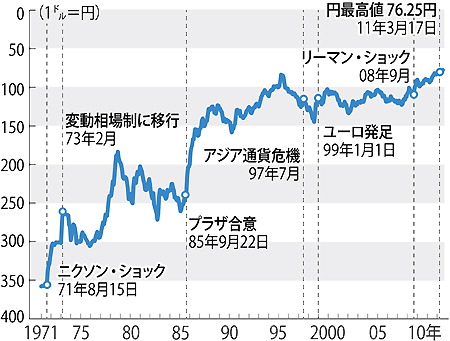

Volcker envisioned that once exchange rates were modified, Bretton Woods would be restored, perhaps with a more flexible mechanism for adjusting rates. He tirelessly negotiated with Europe and Japan, but Bretton Woods could not be put back together. The gold window stayed shut. More devaluations followed, and by 1973, currencies were freely floating.

Friedman’s prediction that, left to the market, currencies would regulate themselves with only gradual adjustments proved wildly incorrect. The dollar plunged by a third during the ’70s, and currency volatility has threatened several national economies since; in 1997, Asian and Latin American countries were wrecked by currency runs. To this day, Volcker regrets that Bretton Woods was abandoned. “Nobody’s in charge,” he says. “The Europeans couldn’t live with the uncertainty and made their own currency and now that’s in trouble.” The effect on America’s domestic economy was even worse. As Shultz says, “Price controls gave the illusion of doing something about inflation.” They further liberated Nixon from concern for the normal rules. Late in 1971, he wrote to the Fed chief, “You have given me absolute assurance that money supply growth will be adequate to maintain growth.” Burns scrawled in the margin, “Never gave him absolute assurance. What nonsense!” But Burns, intentionally or not, delivered on Nixon’s demand for an expansionary monetary policy.

Controls had the desired short-term effect; inflation was quiescent through the end of 1972, when Nixon easily won reelection. The controls, however, proved difficult to end. The 90-day freeze begat a more complicated wage and price regime, a Phase II, followed by a Phase III, lasting into ’74. And Burns’s easy money fostered a monetary steam cooker that controls could not suppress. By August ’74, when Nixon resigned, inflation had topped 11 percent. Soon it would go even higher. Expectations of rising prices became embedded in the system.

The Nixon Shock was a central cause of the Great Inflation. It also spelled the end of the fixed relationships that had governed the financial universe. Previously, people took out mortgages for set periods and at fixed rates. They had virtually no options for saving money other than in banks, and the interest rates that banks could pay were capped. Floating currencies unleashed a new world of risk and instability. For the first time, investors could bet on the direction of interest rates or the Swiss franc. New financial instruments, new speculative tools, proliferated. The world gravitated from the certainties of Bretton Woods to the dizzying market cycles we’ve lived with since. Donald Kohn, who joined the Fed in 1970 and retired last year as vice-chairman, thinks Bretton Woods was doomed. But bankers have yet to find as rigorous a standard as gold. And they have become ever more apt to please politicians, deferring recessions at the risk of inflating asset bubbles.

Burns was replaced by Jimmy Carter in 1978. The following year, with

inflation rocketing toward 15 percent, Burns delivered a keynote speech, “The

Anguish of Central Banking,” in which he argued that central bankers around the

world were failing because elected leaders were unwilling to risk displeasing

constituents. The new Fed chief, Volcker, did tame inflation; unlike Burns, he

had the fortitude to subject the country to a brutal recession. But the dilemma

faced by Burns—how to withstand the demands of the public for limitless monetary

expansion—did not go away. We see it now in the troubles of nations from Greece

to Ireland to the U.S. And the anguish that Burns felt is Ben Bernanke’s

unfortunate inheritance.

英文記事URL:BUSINESSWEEK.COM(2011年8月4日配信) http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/the-nixon-shock-08042011.html